Volume 20, Issue 44 (November 4, 2018)

Belshazzar and Darius the Mede:

Was Daniel Wrong?

By Kyle Pope

A favorite target of critics of faith concerns two kings mentioned eight times each in the book of Daniel: Belshazzar and Darius the Mede. The first is the Babylonian king whom Daniel records was feasting when Babylon fell (Dan. 5:1-30) and during whose reign he received two visions (Dan. 7:1; 8:1). The second is the Median King who took Babylon from Belshazzar (Dan. 5:31), threw Daniel in the Lions’ Den (Dan. 6:1-28), and during whose reign Daniel also received a vision (Dan. 9:1; 11:1).

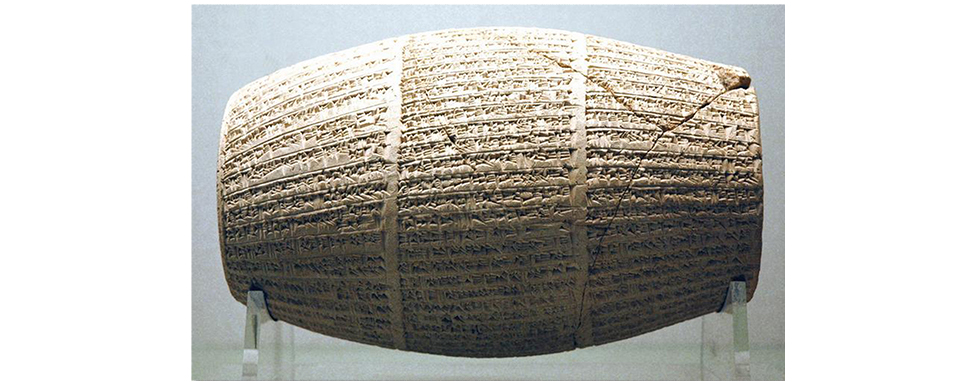

The Cyrus Cylinder

The Problem

Unfortunately much of secular history does not record the existence of either of these figures. For example, the Uruk King List (Tablet IM 65066), an Akkadian tablet listing kings from the Assyrian King Assurbanipal to the Seleucid King Seleucus II, lists Nabonidus as the last Babylonian king and Cyrus the Great as the first Medo-Persian king. This has led some to conclude that neither of these kings mentioned in Daniel actually existed and Daniel was wrong.

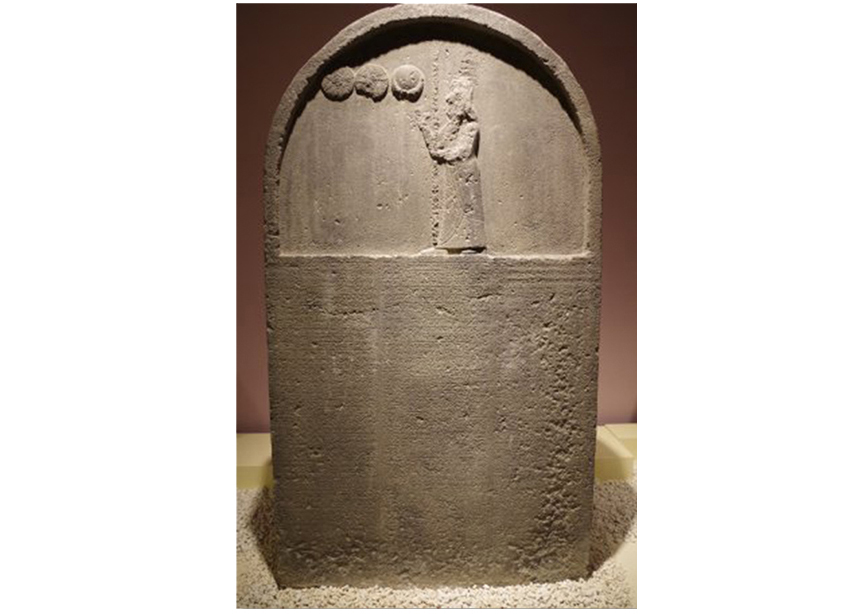

The Nabonidus Cylinder from Ur

The Discovery of Belshazzar

There is no question that Nabonidus is mentioned prominently in ancient texts describing the end of the Babylonian Empire. The Cyrus Cylinder (British Museum 90920), for example, an Akkadian clay cylinder written around 539 BC and placed in the foundation of a Babylonian temple, records Cyrus the Great’s claim that he defeated Nabonidus because of his irreverence towards the god Marduk (17). This led some to conclude that Belshazzar and Nabonidus must have been the same person. Josephus, the first century Jewish historian drew that conclusion (Antiquities 10.11.2), but that changed in 1854. Archaeologist J.G. Taylor found four Akkadian cylinders written by Nabonidus around 540 BC in connection with repairs he had made to the temple of the moon god Sin in Ur. On the cylinders Nabonidus prayed for “Belshazzar, the eldest son, my offspring”1 When speaking to Belshazzar, referring to Nebuchadnezzar, Daniel used the expression “you his son, Belshazzar” (Dan. 5:22). Nabonidus and Belshazzar were not of the biological lineage of Nebuchadnezzar, but Daniel used “son” in a figurative sense. So, why would Daniel call him “Belshazzar the king” (Dan. 5:1)? An Akkadian inscription known as the Verse Account of Nabonidus (believed to have been written during the reign of Cyrus the Great) claims of Nabonidus, “he entrusted the army to his oldest son, his first-born, the troops in the country he ordered under his command. He let everything go, entrusted the kingship to him, and, himself, he started out for a long journey. The military forces of Akkad marching with him, he turned to Temê deep in the west.”2 Belshazzar was entrusted with the authority of kingship in his father’s absence. This is further supported by another text know as the Nabonidus Chronicle, which speaks of the “prince” being left in Babylon while Nabonidus was frequently away.3 It is believed that Babylon fell while Nabonidus was away from the city and Belshazzar, his coregent, was in charge. This explains well why Daniel was offered to become “the third ruler in the kingdom” (Dan. 5:16). Belshazzar was a king, but could only offer Daniel the position as “third ruler” because his father was first and he was second. Today, few still question the existence Belshazzar. Daniel was accurate all along.

The Nabonidus Chronicle

Darius the Mede: A Modern Problem

Unlike the question of Belshazzar, until modern times there really wasn’t much controversy over identification of “Darius the Mede.” Two ancient writers had spoken of a “Darius” that ruled before Cyrus the Great, who was distinct from Darius Hystaspes (the third king after Cyrus, and father of Xerxes). The first was Berossus, a Babylonian historian who lived in the third century BC. His works, though widely known in the ancient world, now survive only in quotes by other authors. In the Armenian translation of the Chronicle of Eusebius, he is quoted to refer to a “king Darius” who held power before Cyrus the Great (“Chaldean Chronicle” 11).4 Second, was a Greek grammarian named Harpocration who lived in the second century AD. In a lexicon he wrote on ten Greek orators, he defined the meaning of the word “daric,” a Persian coin. He wrote, “darics are not named, as most suppose, after Darius the father of Xerxes, but after a certain other more ancient king” (Lexeis of the Ten Orators Δ 5, Δαρεικός).5

Xenophon

In addition to this, the Greek historian Xenophon (ca. c. 431-354 BC), who served as a mercenary in the Persian army a century after Cyrus the Great, wrote a work called the Cryopedia (or The Education of Cyrus). This work told of a king of the Medes named Astyages, who was the grandfather of Cyrus the Great (1.2). Xenophon claimed when Astyages died, he was succeeded by his son Cyaxares II (1.5). At this time, a confederacy existed between Media and Persia, with Persia the inferior partner in the relationship. He claimed that Cyrus took Babylon for the confederacy while Babylon was feasting (7.5.15). After taking Babylon, Cyrus went to Cyaxeres II telling him that he had prepared a palace for him in Babylon (8.5.17). Cyaxeres II, having no male heir, then gave Cyrus his daughter as a wife and “all Media as a dowry” (8.5.19). The Greek playwright Aeschylus (ca. 525-455 BC) gave support to this view. He considered Cyrus the Great the third successor to two Median kings that preceded him (Persians, 766). For centuries, this led many to conclude that Cyaxeres II was the same king Daniel called “Darius the Mede.” Josephus wrote, “Babylon was taken by Darius, and when he, with his kinsman Cyrus, had put an end to the dominion of the Babylonians, he was sixty-two years old. He was the son of Astyages, and had another name among the Greeks” (Antiquities 10.11.4). Jerome (AD 347-420) in his commentary on Daniel, wrote that Cyrus the Great, “succeeded his maternal grandfather, Astyages, and reigned over the Medes and Persians along with his uncle, Darius, whom the Greeks called Cyaxeres” (comments on Daniel 8:3).

Herodotus

This understanding began to change in the nineteenth century. Unfortunately, conflict exists among some of the Greek historical sources. For example, although he claimed to know four versions of the account of Cyrus’ rise to power, the Greek historian Herodotus (ca. 484-425 BC) wrote only one of them (Histories 1.95).6 He agreed with Xenophon that Cyrus was the grandson of Astyages, but claimed that he had no male heir (1.108-109). Herodotus claimed that Cyrus deposed Astyages, but treated him with “great consideration and kept him at his court until he died” (1.130). Another Greek historian named Ctesias, who was a contemporary of Xenophon and served as a physician for the Persian royalty claimed Herodotus was a “liar,” and offered yet another account of Cyrus’ rise to power. He agreed with Herodotus that there was conflict between Cyrus and Astyages, but denied that they were related (only that Cyrus “adopted him as a father”) and mentions a son (or stepson) of Astyages named “Parmises” who had three sons. According to Ctesias, Astyages starved to death while under custody (from the Persica, preserved in Diodorus of Sicily, Bibliotheca Historica 2.32.4 and Photius, Bibliothèque 35b.35-36a.8).7 This made it difficult to establish which source best reflects what really happened.

Nabonidus Cylinder from Sippar

In the nineteen century a number of Persian and Babylonian inscriptions were found, which were largely propaganda texts written after Cyrus’ rise to power. The Cyrus Cylinder, for example, only mentioned Cyrus taking Babylon (18-21). The Nabonidus Chronicle and the Nabonidus Cylinder from Sippar both claim Astyages fought with Cyrus and was taken prisoner. Given that much of the scholarly world was adopting an anti-supernatural liberal attitude toward the Bible, led many to accept Herodotus’ version without question, Xenophon’s version as fiction, and thus reject Daniel’s “Darius the Mede” as unhistorical.

Median and Persian Officials from Relief at Persepolis

Reappraisal of the Situation

It shouldn’t surprise us if propaganda inscriptions emphasize the most prominent figures—that’s their function. However, for the critic to claim that Daniel was either ignorant or deliberately concocting a fictitious account ignores the facts of the situation. Secular history presents conflicting accounts of the Medo-Persian union. Was Media a conquered subjugated kingdom when Babylon fell or part of a confederacy that merged through peaceful intermarriage and family succession? The student of Scripture will recall that even as late as he time of Esther, appeal is made to “the laws of the Persians and the Medes” (Esth. 1:19). Ruins of the Persian palace at Persepolis from the time of Darius Hystaspes show Persian and Median dignitaries ruling together, not merely subjugation, but a merging of cultures.

In 1985 classicist Steve W. Hirsch wrote two important works challenging the rejection of Xenophon’s account of Cyrus as pure fiction.8 In 2014 building on these works, Steven D. Anderson, while at Dallas Theological Seminary wrote his doctoral dissertation reevaluating this evidence. This has now been published under the name Darius the Mede: A Reappraisal (Grand Rapids: Amazon/CreateSpace, 2014). Anderson argues that the scholarly world moved far too quickly to reject the identification of Cyaxares II with “Darius the Mede.” He appeals to much of the evidence cited above, but also considers two significant pieces of inscriptional evidence that support this conclusion.

The Behistun Inscriptions

1) The Behistun Inscription. This is a large, multi-language relief carved into a cliff on the Behistun Mountain in western Iran. It commemorates Darius Hystaspes (the third king after Cyrus). In two instances it mentions imposters who claimed the right to rule the Medes because they were of the “family of Cyaxeres” (2.24; 2.33). Cyaxeres I was the father of Astyages, but the question arises, if Astyages was the last king of the Medes why wouldn’t they appeal their lineage to him? On the other hand, if Cyaxeres II (Astyages’ son) was meant, they would be appealing to the last king of the Medes (29).

The Haran Nabonidus Stele

2) The Harran Nabonidus Stele. This inscription recounts deeds of Nabonidus, but is believed to have been written after the date that most scholars believe Cyrus dethroned Astyages, but before the fall of Babylon. In it, Nabonidus refers to kings who urged him to return to Babylon. He lists “the kings of the land of Egypt, of the land of [the city of] the Medes, of the land of the Arabs, and all the kings of hostile (lands) were sending to me for peace and good (relations).” Anderson argues, “The Harran Stele thus offers strong support for the existence of Xenophon’s Cyaxares II (and Daniel’s Darius the Mede) by implying that there was a king of the Medes whom Cyrus did not overthrow” (95).

If this is correct the critic has no grounds on which to claim that “Darius the Mede” did not exist. Like Belshazzar, what Daniel wrote was accurate all along. “Darius the son of Ahasuerus, of the lineage of the Medes” (Dan. 9:1), is the last king of the Medes known to the Greeks as Cyxares II, the son of Astyages.

4 The text reads, “When Cyrus captured Babylon, he made Nabannidochus [i.e. Nabonidus] the governor of Carmania; but king Dareius [i.e. Darius] took some of the territory away from him” (http://www.attalus.org/translate/eusebius4.html). Eusebius attributes the exact quote to the Greek historian Abydenus (second century AD), but Anderson argues that Eusebius shows that Abydenus was dependent upon the Greek scholar Alexander Polyhistor (first century BC) who was dependent upon Berossus (107).

5 The tenth century Byzantine lexicon known as the Suda made the same claim (Δαρεικούς).

6 The orator Isocrates (436-338 BC) offers yet another version, claiming Cyrus killed Astyages (Evagoras 9.38).

8 Steve W. Hirsch, The Friendship of the Barbarians: Xenophon and the Persian Empire (Hanover NH: University Press of New England, 1985) and “1000 Iranian Nights: History and Fiction in Xenophon’s Cyropaedia”, in The Greek Historians: Literature and History: Papers Presented to A. E. Raubitschek (Saratoga, CA: ANMA Libra, 1985), pp. 65-85.